Highlights

Table of Contents

Explore article topics

You have your story, your cast, your crew, your gear and lighting; you have a set or location. You’re just about ready to go. What you have to think about now is your scene composition. Good composition can make or break a film because you can’t just put everyone and everything in a room and leave it at that. Where people and things are positioned in a scene and how you approach filming them conveys so much to the audience. It doesn’t matter if you’re shooting a tell-all interview or making a dance video, understanding composition techniques and using them effectively will bring your filmmaking to life.

Rule of thirds

The chances are that if you’ve only heard of 1 compositional rule, it’s the rule of thirds. This rule divides your scene into 9 rectangles, using 2 vertical lines spaced evenly across your scene and 2 horizontal lines at equal intervals down your frame. The 4 points where these lines intersect are called points of interest or power points.

The theory behind the rule of thirds is that you position your subject of focus on one of the points of interest and use the dividing lines for strong horizontal or vertical lines in your scene. This creates a strong dynamic within the frame and introduces tension between the elements in the scene. Unless you are looking for a specifically symmetrical composition, framing your subject in the center of the scene can feel flat and lifeless. It doesn’t really matter which focal length you are using, you can still apply the rule of thirds.

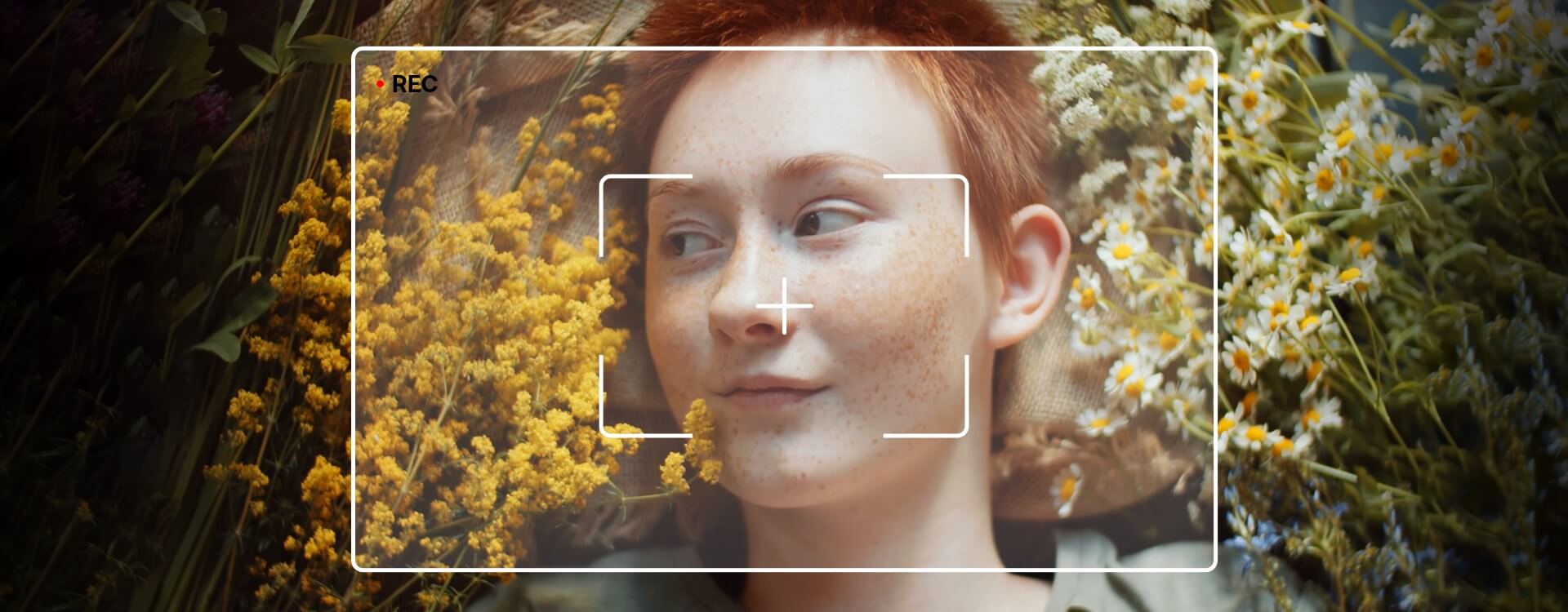

You can see in this video how the subject is positioned on the second vertical, with her head on the top-right point of interest.

In this video clip, the headland in the background sits along the upper horizontal line. It doesn’t run through the center of the frame, which would cut it in half and leave the scene feeling flat.

Balance and symmetry

Balance and symmetry are different composition techniques. Balance comes in many forms, but it ensures that a cinematic composition feels complete. A figure with its head on the upper left point of interest can be balanced by an object toward the bottom right. It doesn’t need to be the same size, shape or color but it provides a complement. A deep pink flower in the upper right corner of a shot can be balanced by bright green negative space filling the rest of the scene. Or someone in the lower right can balance themselves by looking toward the upper left corner. You’ll feel an unbalanced scene when you see one, whether you’ve used a telephoto or a wide-angle lens. Be open about how you rebalance it – it isn’t necessarily the obvious choice that will work the best.

Supposedly, the more symmetrical people are, the more attractive we find them. I’m not sure how strictly accurate this is, but it does help explain why we find symmetrical shots pleasing to the eye, even if they do break the rule of thirds. There’s a calm, evenness to them that’s engaging.

For certain shots, only symmetry will do – for example with this footage of a quad scull. And centered shots of people’s faces are alluring: You feel as if you can connect with them. They are very powerful and can be accentuated by moving in or out toward the subject using a dolly shot.

2 tips when it comes to symmetrical compositions: First, they need to be accurate. If they are not quite right, they will irritate your viewers. Second, do not overuse symmetrical composition. It can become exhausting for your audience or lose its impact.

Leading room and headroom

Headroom means leaving a gap between the top of your subject’s head and the edge of the frame. This prevents the scene from feeling cramped or maybe rushed or aggressive. There might be times when evoking those feelings is exactly what you need, but mostly, give your subjects room to breathe in the scene.

Leading room refers to the position of the subject in your scene and the direction they look in. Convention suggests that if you have a subject on the left of the scene, they should be looking to the right, not the left, of the frame or it can feel confusing for the audience. If you do it carefully and with consideration, I think this is a rule that’s good for breaking.

Leading lines

You start at the tree and then follow the path through the scene.

Leading lines direct your audience to your point of focus or to something else in your scene that is somehow significant. Leading lines can be real or imaginary, straight or curved. Roads, railway tracks and rivers are all obvious leading lines, but people’s lines of sight work, too. Where is your subject looking? Where they look, your audience will look, too.

You might look to the filmmaker on the cliff initially, but you will then follow his line of sight down to the sea.

It’s possible to compose a shot using multiple leading lines that draw you through the scene and help in telling your story. A path could lead to your subject, while their sightline could lead up to a tree to a bird.

Depth of field

How much of a scene is in sharp focus and how much is blurred helps to tell your story by showing your audience where to concentrate and what’s important.

A shallow depth of field is great for concentrating your audience’s attention but it won’t work for an establishing shot where you are trying to set context. Even with a wide-angle lens and a deep depth of field, you can still ensure your audience recognizes your subject. By making the subject smaller or larger in the scene, you can suggest if someone is overwhelmed or in control of a situation, too.

Learning how to pull focus or rack focus is a great skill to help switch what’s in focus in a scene. Whether you are using a prime or zoom lens, it will need to have a manual focus for rack focusing.

180º rule

When you have 2 or more characters communicating within a scene or a character interacting with a key object, they should always remain on the same side of the screen as the audience looks at them. This is called the 180º rule and helps to maintain consistency for your audience. You can cross the 180º line, but this needs to be done very carefully and with purpose, otherwise, it will confuse the audience, and they can lose the plot.

Get unlimited royalty-free 4K footage

Direction and levels

Camera angles change how an audience feels about the subjects on screen. If you approach someone at eye level, your audience will feel equal and connected to them. Film from below, and the audience will feel submissive to the character. Reverse the filming position and the character will come across as submissive. Remember, as you change your shooting angles, what appears in your foreground and background will change, too. You must consider what you want to be visible and how significant it should be.

Compared to

Know the rules, so you can break them

You might well be told that the difference between good composition vs bad composition is adhering to the composition rules. This isn’t true. When you understand the rules of composition it gives you a deeper understanding of how your audience will interact with your footage. And this gives you the liberty to go and break the rules to achieve your filmmaking goals. The difference between good scene composition and poor frame composition is whether or not you are able to tell your story in a compelling way that grips the audience and doesn’t distract or irritate them. Be bold. Know the rules of composition and then you can break them properly.

Daniela is a writer and editor based in the UK. Since 2010 she has focused on the photography sector. In this time, she has written three books and contributed to many more, served as the editor for two websites, written thousands of articles for numerous publications, both in print and online and runs the Photocritic Photography School.

Share this article

Did you find this article useful?

Related Posts

- By Daniela Bowker

- 18 MIN READ

- By Josh Edwards

- 5 MIN READ

Latest Posts

- 25 Apr

- By Josh Edwards

- 4 MIN READ