Highlights

Table of Contents

Explore article topics

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we’re taking a look at the work of 7 brilliant women directors and seeing how they each give a unique look and feel to their work. Of course, there are many more than just 7 amazing women directors out there, but we have to start somewhere!

Kathryn Bigelow, The Hurt Locker (2008)

Let’s start with Kathryn Bigelow, the only woman to win a Best Director Oscar and the film that earned her the Academy Award, The Hurt Locker. Bigelow worked with her director of photography, Barry Ackroyd, to create a film that feels as if it were a documentary shot by an embedded journalist in Iraq. Using Aaton 16mm cameras with Fujifilm stock, the overall sense is one of instability, enhanced by using handheld cameras. There is lots of zooming in and out and quick focus changes that reflect the dangerous and fast-changing environment of the assignment.

The Iraq scenes, which were actually filmed in Kuwait, were primarily shot during the day using as much natural light as possible. Ackroyd has said that he prefers lighting that doesn’t interfere with acting, and that follows through to the few night scenes, which mostly made use of practical lights.

Many of the scenes in Iraq use a shallow depth of field, suggestive of the tight focus and narrow objectives of the characters who are bomb disposal experts. This is in contrast to the scenes in the USA, when the protagonist has returned from his tour of duty where the aimlessness of his new life is conveyed through wider shots with a deeper field.

The transition from Iraq to the USA is not a smooth and easy one for the protagonist, which is reflected in the quick cuts between the 2 countries. Bigelow’s use of sharp contrasts in filming style, camera angles and lighting between Iraq and the USA drives home the difficulty in adjusting from military to civilian life. It’s a good example of how technique is a critical element in your storytelling.

Céline Sciamma, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

Reviews of Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire were near-universal in their praise of a beautiful painterly film that was all about the female gaze, or point of view. Given that it tells the story of a woman assigned to secretly paint the portrait of a bride-to-be for her intended husband, the acclaim could not be more apt. Sciamma and her cinematographer, Claire Mathon, researched historical women artists and their work to bring authenticity to this period piece.

Sciamma made use of long, lingering shots that required very careful blocking and choreography, but not much alteration of setups. This contributes to the ‘slow burn’ buildup of the film, but also allows the lighting to really shine.

Sciamma had very clear ideas about using the type of light that referenced the oil paintings from her research. She wanted an overwhelming sense of softness to the light that never took over. The actors’ skin does not have a realistic look to it, but instead resembles the matte perfection of oil painting portraits. In Sciamma’s words: ‘The light would seem to come out of the character.’

The interior scenes were shot in a castle in the Seine-et-Marne region of France. The age and unrestored nature of the castle meant that the crew needed a different approach to the lighting. They constructed a platform outside the castle and lit all the scenes through its windows. All of the nighttime scenes were lit with what looked like candlelight but without any candles being used. This all gave a very sensual feel to the scenes and helped to create that other-worldly light.

Behind the scene of ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’. Image by NEON

The beach scenes were all shot on the Brittany coast, and while the cast and crew were expecting wind and rain, they had brilliant sunshine. They used a Red Monstro camera with Leitz Thalia lenses and a film-look LUT. The film-look enhanced the cyan tones in the shots, which contrasted well with the actors’ red and green dresses and brought bold and intense colors to the film.

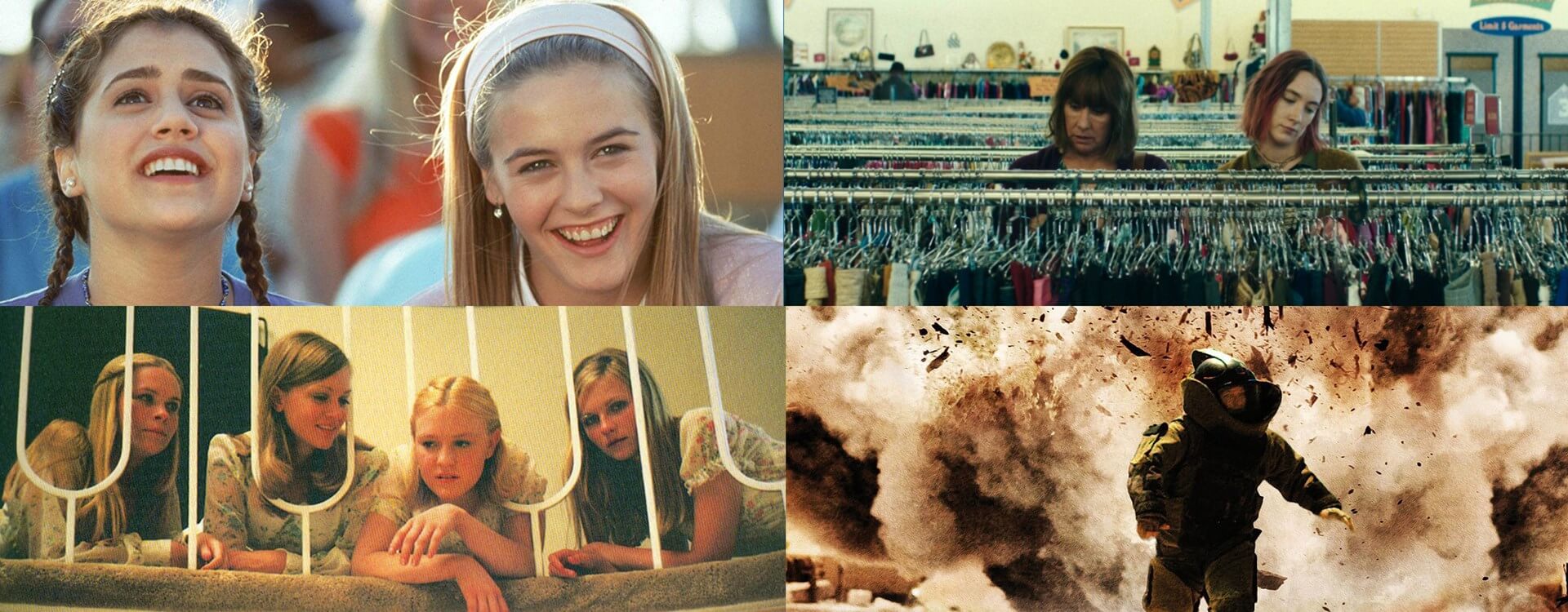

Sofia Coppola, The Virgin Suicides (1999)

In contrast to the intensely female perspective of Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, we come to Sofia Coppola’s directorial début, The Virgin Suicides. This dreamy-looking film is told retrospectively, with a group of men recalling what they remembered of the 5 Lisbon sisters, all of whom took their own lives. It would be very easy for this film to slide into sentimentality, but Coppola keeps the complexities of the girls’ lives in the foreground, and you wonder how reliable the narrators truly are.

Contrasting against the soft and young look of the film with lots of pastel colors is the melancholy of the soundtrack. This juxtaposition emphasizes the confusion surrounding the girls’ lives and the boys’ understanding of it. What really happened? And why?

Key to Coppola’s storytelling technique is her use of window shots. In particular, we see the girls gazing from a large window of their home, the camera looking back at them and the outside world reflected in the glass.

Who is watching and who is being watched becomes interchangeable. Another window shot that Coppola used in The Virgin Suicides and in her later movies, for example Marie Antoinette, Lost in Translation and Somewhere, was the car (or carriage) window shot. They all show people being taken somewhere but without giving away where and why? It’s an emotive storytelling tool.

Andrea Arnold, Fish Tank (2009)

You will often hear that Andrea Arnold’s filmmaking belongs to the tradition of ‘British social realism,’ along with Ken Loach and Mike Leigh. Arnold, though, prefers to think of the audience as dropping in on people’s lives, rather than being on the outside and looking in. This is something that she achieves through her filmmaking approach.

For a start, Arnold often mixes non-actors and actors. In Fish Tank, the teenaged lead Mia was played by Katie Jarvis, who was offered the part after Arnold saw her waiting for a train. Arnold felt that Jarvis embodied Mia and felt authentic to her vision. But Conor, the character with whom Mia falls in love, was played by Michael Fassbender.

Next, Arnold prefers to shoot sequentially. She likes the organic flow that this creates in a film and how it allows actors to develop their characters over the course of the project.

Arnold doesn’t tend to block scenes or devise a shot list, either. Lens choices can often be down to chance, too. But she does prefer 35mm film over digital. All of these choices help to contribute to the natural feeling that her films depict real life. Along with DP Robbie Ryan, Arnold succeeds in immersing you into her characters’ lives. And just as the scenes where Conor touches Mia play out more lyrically than the hard bite of real life, it’s as if we have slipped off into a daydream.

Lynne Ramsay, We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

While Lynne Ramsay has certainly made films that fall into the ‘British social realism’ category, We Need to Talk About Kevin takes a step to the side from that. As Ramsay says, it’s not a realist film, it’s a ‘What if?’ film.

We Need to Talk About Kevin tells the story of Kevin, a boy who goes on a murderous rampage, and his mother, Eva. As you might expect, this is a deeply disturbing and disconcerting film, and everything that Ramsay and cinematographer Seamus McGarvey put together on screen contributes to that sense of dread and terror. It was mostly shot using a 35mm camera on Fujifilm stock with the flashback scenes being digital.

You might never see blood or gore, but the red motif runs very strongly through the film, and the sense of horror is very carefully psychologically crafted. When light flares are used to signal violence, what is left to the imagination is very much worse than anything that could be shown on screen.

Ramsay used elliptical editing to tell the story that was originally an epistolary novel (in the form of letters), with the flashback scenes having a flatter and softer look with less color than those set in the present. For the present, very bold primaries–red, blue and yellow–contribute to the intensity of the story, as does the use of close-up shots and of characters positioned at opposite edges of the frame. It’s a confrontational look, but it also highlights the distance between them.

Together with the intense coloring, the soundscape is harsh, reflecting Eva’s confused and devastated state of mind. The color and the sound also work to build up the tension for the viewer.

Finally, it’s also worth noting the visual similarities between Eva and Kevin. Of course, it’s not unusual for children to look like their parents, but in this context, it draws you to reflect on just how much of Kevin’s behavior is nature and to what degree it’s nurture.

Get unlimited royalty-free 4K footage

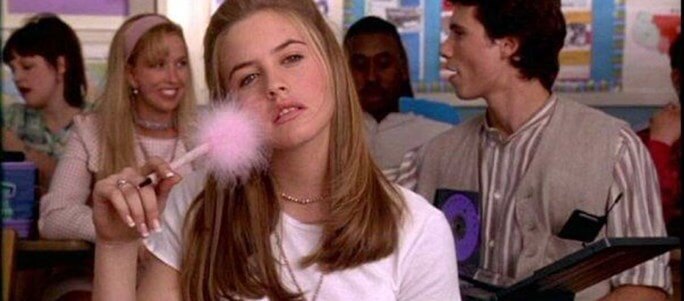

Amy Heckerling, Clueless (1995)

When you think of Amy Heckerling’s 1995 Clueless, you might think of it as a classic of the high school genre. You might remember it for its quirky catchphrases, fantastic fashion and cute soundtrack. You might even remember it for sparking the ‘classics retold’ era leading to films like 10 Things I Hate About You and Cruel Intentions. But there’s a lot more to it and to Heckerling’s filmmaking than that.

Clueless is an archetypal coming-of-age drama that doesn’t shy away from the complexities of relationships, even if it is told at a dizzying, frenetic pace. There’s background action, foreground action, narration and music all happening at once. It would be easy for it all to be overwhelming and for the audience to just want to walk away from it. But in fact, the chaos is carefully choreographed and it clearly reflects a teenager’s life. This brings realism to the otherworldliness of protagonist Cher’s Beverly Hills upbringing.

Cher and her friends’ lives are so privileged and they are so oblivious to their fortunate circumstances, it would be easy to feel disdain toward them. Instead, you love them. Much of that is down to Herckerling’s use of voice-overs. Frequently, what you hear Cher telling you is completely at odds with the visuals on screen. But it’s her sincerity and genuine belief in the situation that wins you over. She’s not malicious; she’s loveable.

Heckerling wanted Clueless to be all ‘sparkle and glitter’. Apart from her own dislike for dimly lit scenes after growing up in a dark Bronx apartment, she had seen so many filmmakers head toward the Rembrandt-y look with their lighting that she wanted something different. Together with cinematographer Bill Pope, Heckerling gave us just that; they take you into a positive world filled with light and laughter. And Clueless would never have worked without the outfits, the lighting design, or the exploding fountain in the background when Cher finally realizes whom she loves.

Greta Gerwig, Lady Bird (2017)

Lady Bird is meant to feel like a memory. However, Gerwig didn’t want her directorial début to have the commonplace look of out-of-the-box grain or soft focus that typifies memory. Instead, she wanted her audience to feel the proscenium arch and to sense the magic of the lightbox of cinema. The effect that she and cinematographer Sam Levy conjured, using an Arri Alexa Mini with old Panavision lenses and shot in 2K, resembled printed pages that had then been photocopied, or photocopies of photocopies. It feels as if you’re looking at something where there’s a clear loss of quality, but it’s not over the top.

Gerwig drew more inspiration from photos of young women by Lise Sarfati taken in the early 2000s. The description that drove the look of Lady Bird was ‘plain but luscious’. She wanted the set and the costumes to be rich and well-rounded but not so that they distracted the viewer. Everything is there to contribute to the person of the character or to the story itself, but nothing is meant to take charge.

Finally, there’s the dialog. It’s meant to feel ‘real’. The characters in Lady Bird speak in sentences that change direction, or don’t actually go anywhere or really stop. There are interruptions. It was scripted but it was scripted to sound how people converse in real life, not to sound like a film script. The focus of Lady Bird is on the characters and their story; it’s not on the set or on flashy cinematography. It’s about real life.

Daniela is a writer and editor based in the UK. Since 2010 she has focused on the photography sector. In this time, she has written three books and contributed to many more, served as the editor for two websites, written thousands of articles for numerous publications, both in print and online and runs the Photocritic Photography School.

Share this article

Did you find this article useful?

Related Posts

- By Josh Edwards

- 6 MIN READ

- By Alice Austin

- 5 MIN READ

- By Daniela Bowker

- 7 MIN READ

Latest Posts

- 25 Apr

- By Josh Edwards

- 4 MIN READ